In Marzano, Pickering, and Pollock's 2001 meta-analysis, McREL researchers found an effect size for feedback of 0.76, which translates roughly into a 28-percentile point difference in average achievement (Beesley & Apthorp, 2010; Dean, Pitler, Hubbell, & Stone, 2012). John Hattie (2009) found a similar effect size of 0.73 for feedback in his synthesis of 800 meta-analyses of education research studies; in fact, feedback ranked among the highest of hundreds of education practices he studied.The bottom line here is that feedback matters in the context of learning. It should also be noted how it differs from assessment. Feedback justifies a grade, establishes criteria for improvement, provides motivation for the next assessment, reinforces good work, and serves as a catalyst for reflection. The assessment determines whether learning occurred, what learning occurred, and if the learning relates to stated targets, standards, and objectives. In reality, formative assessment is an advanced form of feedback.

In my opinion, you can never provide learners with too much feedback. However, the way in which it is delivered matters significantly. Nicol (2010) found that feedback is valuable when it is received, understood and acted on. How students analyze, discuss and act on feedback is as important as the quality of the feedback itself. I couldn’t agree more. In a recent post I identified the following five components of good feedback:

- Positive delivery

- Practical and specific

- Timely

- Consistency

- Using the right medium

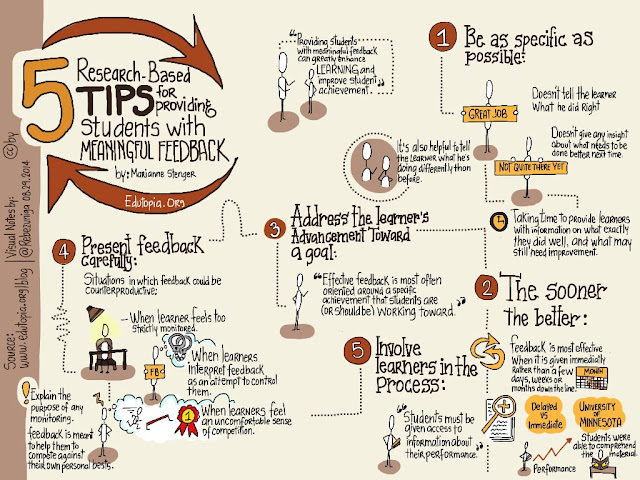

For some more research-based tips on providing students meaningful feedback check out this Edutopia article by Marianne Stenger and the excellent image below.

Think about all the conversations that educators have with learners on a daily basis. The valuable information in many cases aligns with what the research has said constitutes good feedback. The problem though is the reasonable possibility that learners forget what they have been told regarding progress or improvement and they don’t have the ability to later reflect on the feedback that was given. You know how the saying goes, out of sight out of mind. Having students create a feedback log solves this issue by helping them remember, retain, reflect upon, and chart their progress of improvement. Best of all it requires no extra time on the part of the teacher.

A feedback log can be created in many ways and aligned to skills, concepts, or standards. Students can then use this as a means to track their progress and growth over time as more feedback is provided over the course of the year. If students genuinely own their learning, then they must be put in a position to reflect and then act on the feedback they are given. The use of a log can also strengthen partnerships with parents. By making them aware of the log, parents have an opportunity to be more involved in their child’s learning each day.

Implementing feedback logs as a part of consistent professional practice saves precious time, can be seamlessly aligned with research-based strategies, will help students monitor their understanding of essential learnings, and can be used to provide more targeted support to those students who don’t show reasonable growth over time. Best of all they can serve as an empowerment tool to help kids exert more ownership over their learning.

Nicol, D. (2010). From monologue to dialogue: improving written feedback processes in mass higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in

Higher Education, 35(5), 501-517.

You need to be a member of School Leadership 2.0 to add comments!

Join School Leadership 2.0