How to stay focused on rigor and engagement even when your best-laid plans fall apart

When I first started teaching, back-to-school was always a complicated time. I was excited by the chance to turn the page on a new year and do things better than I had the year before. I was eager to get my supplies and organize my classroom with its freshly buffed floors.

And I found satisfaction in the deep and sustained focus I could give to my curriculum in the summer. I loved greeting my students knowing that I had a month of lessons in my back pocket.

But as soon as those students walked through the door, things always got complicated! Not only were they messy (not caring about my perfect, shiny floors), they often didn’t respond in the way I expected to the lessons I had planned.

Their background and skills would sometimes surpass my expectations, but, often, they really struggled. And, always, always they asked me questions and had ideas that took me in unanticipated directions.

The downside of spontaneity

In some ways I loved these moments because their questions and ideas showed that they were engaged, and I enjoyed puzzling through things with them. But getting off track meant that I would often lose sight of the purpose of my lesson.

Unfortunately, rigorous thinking was usually the first thing to get lost in the shuffle. If I had planned for my students to engage in an evidence-based debate, for example, I would sometimes find myself running out of time and skip it in favor of a more straightforward Q and A format.

Spontaneity isn’t necessarily a bad thing; in fact, it’s an essential part of teaching. How could anyone expect things to go as planned when there are 25 students with 25 sets of needs sitting before us? In reality, bending our knees and changing plans is often one of the only things we can really plan for.

Given this reality, how can we ensure that we don’t miss opportunities for deeper instruction that helps students think critically, collaborate, and engage in the kind of scholarly discourse we envisioned for them when we wrote our lessons? These ABCs of deeper instruction may help.

A. Ask Strategic Questions

In many ways, the questions you ask and the questions you answer define what and how students learn in your classroom. For this reason, questions deserve to be planned for strategically so that even if you need to change plans for your lesson as a whole, you can fall back on high-quality questions.

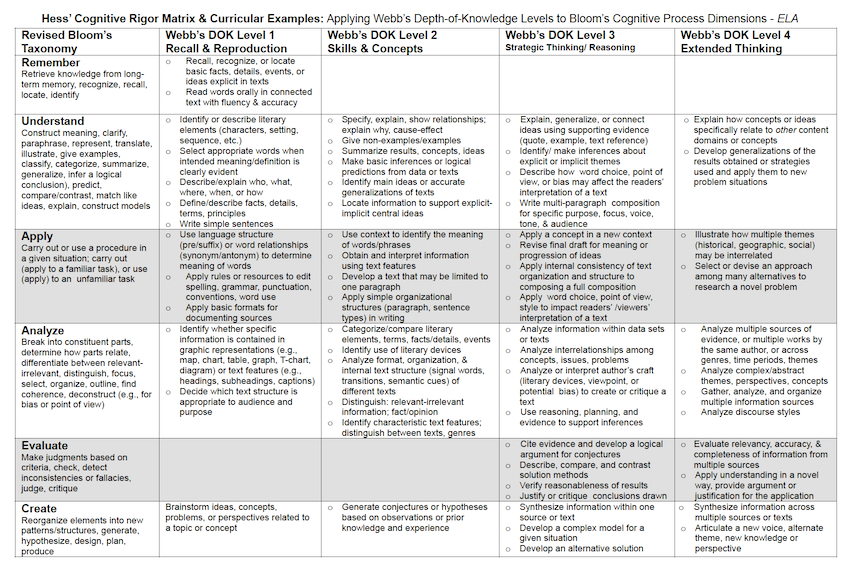

High-quality questions ensure that students move from simple recall to more sophisticated cognitive tasks, like analyzing and evaluating. It may be helpful to think about questions over an arc of lessons rather than just one lesson (e.g., if students are rememberinginformation on Monday, that’s okay, but try to get them analyzinginformation by Wednesday).

Thinking about and evaluating the cognitive rigor of your questions ahead of time will help you avoid asking too many low-level questions in the spur of the moment. Hess’ Cognitive Rigor Matrix is a great tool for mapping out your questions.

It may also help you to develop a list of standard replies to student questions that put the cognitive work back on them and can be used in a wide range of circumstances. For example:

- “Turn and talk about that question in trios. Let’s see if a little conversation can warm us all up and help us find an answer.”

- “That’s an insightful question and we all need to know the answer. I’m going to give all of you five minutes to go back to the text and find evidence that will help you answer it. After five minutes you’ll share your ideas with an elbow partner and then we’ll discuss it as a whole class.”

- “I bet there are multiple places where we could find that answer. As a table group discuss what you think is the best resource and be ready to defend your reasoning.”

In this video, you can see a math teacher who has mastered the art of strategic questions and encouraging kids to grapple. If they look like 3rd graders – they are! But in my experience, the principles apply across the middle grades.

B. Balance Teacher Talk and Student Talk

Often, when the initial components of a lesson take longer than we think, we revert to doing more teacher talk and leaving less time for student talk. Often we do this to keep on track with pacing requirements, to maintain tight control of behavior, or to more efficiently correct misconceptions.

These are real and important considerations. However, it’s possible to be efficient and give students plenty of time to think and do and to engage in quality discourse.

One great way to get students talking to each other, rather than only to you, is to identify a few high-leverage discussion protocolsthat you can teach them to use reliably. It’s important to start with just a few protocols and practice them repeatedly before adding more to your repertoire.

Once students learn their roles and responsibilities during the protocol, and you’ve given them plenty of time to practice, you will likely find that protocols are an effective and efficient way to get students collaboratively making meaning of text, concepts, or ideas. The predictability of the “rules” of protocols, which demand participation from all students, engages students who may otherwise disengage with their learning.

Protocols can range from very simple and short, to longer lesson-length protocols. “Think-Pair-Share” is a classic short protocol in which students think about (or write about) a question or prompt for a minute or two and then share their thinking with a partner for one or two minutes each. After this warm-up, many more students will be ready to share with the whole class.

“Praise, Question, Suggestion” is an example of a longer protocol students can use to give each other feedback on a piece of work.See Praise, Question, Suggestion in action in this video from a middle school classroom.

C. Challenge Your Students to Grapple with Texts, Problems, and Ideas

Challenge is the heart of deeper instruction. A productive challenge stretches students to go beyond what they may think possible, and this stretch leads to new learning.

Absent a structured protocol or plan, the time for students to grapple with texts, problems, and ideas is hard to protect. It is tempting to think that when we “deliver” content to our students through a lecture, for example, and answer questions about that content, that students will learn more efficiently.

However, giving students time to grapple and make meaning firstengages them more deeply and will likely make a lecture more productive and satisfying for teachers and students alike. Students will come to that lecture with questions and insights that are hard to “deliver,” and this is what will help their learning last well beyond the lecture.

In this video, you can see the power of allowing students time to grapple – in this case, with a highly technical scientific figure. We’ve jumped to 11th grade biology class. Once again, grappling is the key to deeper learning, at every grade!

It’s important to approach challenges like we see in the video together with students during class, rather than assigning them for homework, so that students can immediately discuss what they are learning and where they are stuck.

Creating a culture of grappling in your classroom and an ethos of playful exploration will help students approach challenges like these with a courageous spirit of curiosity.

____________________

Libby Woodfin, a former teacher and school counselor, is the director of publications for EL Education. She is an author of several books, most recentlyLearning That Lasts: Challenging, Engaging, and Empowering Students..., co-written with Ron Berger and Anne Vilen. She is also a co-author of the much-praisedLeaders of Their Own Learning (2014).

Libby Woodfin, a former teacher and school counselor, is the director of publications for EL Education. She is an author of several books, most recentlyLearning That Lasts: Challenging, Engaging, and Empowering Students..., co-written with Ron Berger and Anne Vilen. She is also a co-author of the much-praisedLeaders of Their Own Learning (2014).

You need to be a member of School Leadership 2.0 to add comments!

Join School Leadership 2.0