NEW YORK -- People who aren’t friends on Facebook with Faye Rogaski de Muyshondt won’t learn much from her profile. They’ll see she appeared on the Today Show in October, has a husband and a young daughter, and was born in New Jersey but now lives in New York.

De Muyshondt would call this “appropriate” sharing. But on a recent Saturday morning, what she really wanted to discuss with seven fidgety elementary-schoolers was being inappropriate.

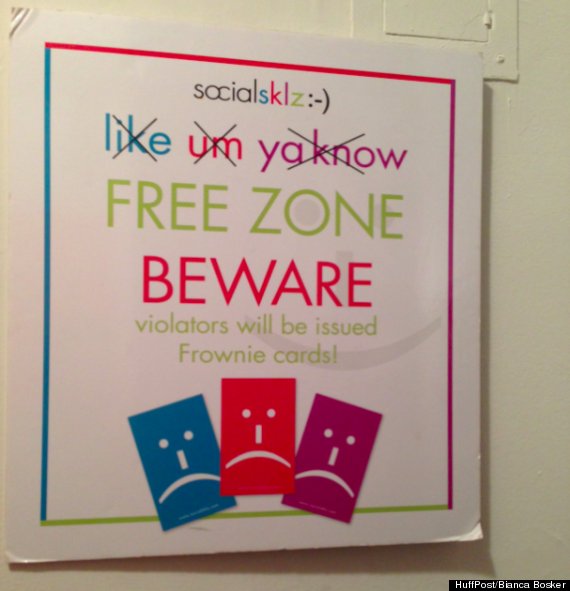

“What do I mean by ‘inappropriate?’” de Muyshondt, whose business socialsklz:-)teaches social etiquette, dared to ask the class. They predictably seized the bait.

“Like a picture of your butt!” squealed one boy in black Adidas sweatpants. Everyone, except de Muyshondt, cracked up at this hilarious gag.

With children now immersed in the Internet from an early age, the tradition of manners classes and Emily Post manuals is, for those who can afford it, being supplemented by more urgent life lessons on how not to destroy your reputation online. Picking the wrong fork is no match for sending the wrong text. And parents are desperate for any way to help their children avoid the career-torpedoing, cyberbully-provoking mishap of someone like Alicia Ann Lynch, the 22-year-old wholast week lost her job and received death threats after tweeting a photo of herself dressed as a Boston Marathon victim for Halloween. Parents are, in de Muyshondt’s words, “really freaked out.”

De Muyshondt has spent her life teaching people how to behave. First, she worked in public relations, reining in adults who acted like children (mostly musicians and company executives). Four years ago, she switched course and founded socialsklz:-), which teaches children how to act like adults.

After receiving a friend request from a client’s 8-year-old daughter, de Muyshondt began offering technologysklz, a $75 course that, in two hours, promises to teach kids ages 9 to 14 how to be ”technologically safe and savvy in a world where the Internet records everything.”

“You don’t send a kid to drive a car without lessons. It’s the same thing for the Internet,” explained de Muyshondt. “You can’t send a kid off to the Internet without lessons.”

Saturday’s lesson was being taught in de Muyshondt’s offices in a converted apartment on the Upper West Side.

“Can I check my email?” one boy, also in black Adidas sweatpants, asked as de Muyshondt passed out a multiple-choice quiz called “How Well Do You Know the Internet?”

She wanted to begin by getting a baseline read on the technology sklz the group of kids, ages 8, 10 and 11, already had. The questionnaire revealed them to know a few things about the Internet: You can join Instagram at any age, but you have to be either 13 or 18 to sign up for Facebook, the class agreed. (It’s actually 13 for both.) Dropbox is only for teachers. (It’s not.) You can get kicked off of the game Animal Jam for sharing your password with a friend, and when you’re playing video games on the Wii, you can use YouTube to find videos that explain how to get past a tricky level. Cyberbullies are people who make fun of kids, say bad words and are so good at using computers, they can “make a photo that never happened and send it to someone else.” It’s easy to take screenshots on an iPhone. And it’s really, really easy to use Instagram to find photos de Muyshondt would call “inappropriate.”

“When we have recess at school, some people take out their phones, they go in the corner and just look at the Instagram. And what you see is the most gross stuff in the world,” explained an 11-year-old boy. “I remember one where -- I’m not trying to describe it, but -- it was people posting stuff of people peeing on the floor and the golden pee.”

De Muyshondt quickly changed course, and tried to call attention to her Facebook profile on the classroom’s flat-screen TV.

“Do you know what Facebook is?” she asked.

“It’s kind of like email, but ... I don’t know,” ventured one of the 8-year-olds.

Another boy cut in. “It’s somewhere where, like, moms and dads, they can type up stuff,” he explained knowingly. “Then, let’s say they type up something for my birthday and they put a picture of me on Facebook, so that all their friends can see it. Then they can comment and ‘like’ it.”

For this group, social media isn’t yet an obsession. Like miniature, sweatpants-wearing CEOs, the kids agreed that email takes up the majority of their time online -- a majority of the group named it as one of the three websites they use the most. It’s where they get homework, someone explained, and, when de Muyshondt later asked them to practice composing emails to their teachers, they completed the assignment handily.

Though they're years away from gaining entry to the Facebooks of the world (unless they decide to lie about their age), the students already had their fair share of Internet horror stories. One described an incident the previous week in which fifth-graders posted pictures they took in the bathroom. Another boy confessed he got in trouble for sending his friend a mean email, which ended up in his mom’s hands. And for one kid, the 11-year-old, joining Facebook was the horror story.

He’d created an account entirely by accident, he said quietly, staring down at his sketchpad. After he got his Yahoo email account, all these things started popping up, and next thing he knew, he’d signed up for Facebook, he explained.

“I didn’t know what to do and I kept on pressing ‘yes,’” he said. “And then I noticed I had Facebook.”

“When I found out I had Facebook, I was like, ‘How do I get out? How do I cancel this thing?’” he added. He still wasn’t sure.

De Muyshondt led the class through a series of exercises, from how to decline a Facebook “friend” request to what not to share with strangers. She went over the defining characteristics of a cyberbully, and then ended by asking all the students to sign an Internet contract. The document included such stipulations as, “I will share with parents things I’m doing on the Internet” and “I will obey any house rules for computer usage.”

A sign posted at the entrance to socialsklz:-)'s classroom.

In the years she’s been working with children, de Muyshondt said she’s seen kids’ offline social skills deteriorate -- an issue she blames on the dwindling amount of in-person socializing they now have growing up.

“By the time I was 20, I probably had five times as much face-to-face interaction as kids today who are 20,” she said. “So I might have made the social mistakes when I was 12 that they’re making now at age 20 or 22, just because I had more time to work through them and practice.”

De Muyshondt left the class with a final bit of advice: Complement your time on the Internet with face-to-face time with family and friends.

One boy raised his hand, puzzled by these instructions.

“What about face time where you’re online but it’s FaceTime?” he asked, referencing Apple’s video chat service. “What about that?”

De Muyshondt had to clarify. “FaceTime,” she told him, “doesn’t count as in-person socializing.”

Posted: 11/14/2013

Huffington Post