School Leadership 2.0

A Network Connecting School Leaders From Around The Globe

One of us was the teacher, the other the student. Mostly what we did was argue.

To fix education, focus on schools where things go right

One of us was the teacher, the other the student. Mostly what we did was argue.

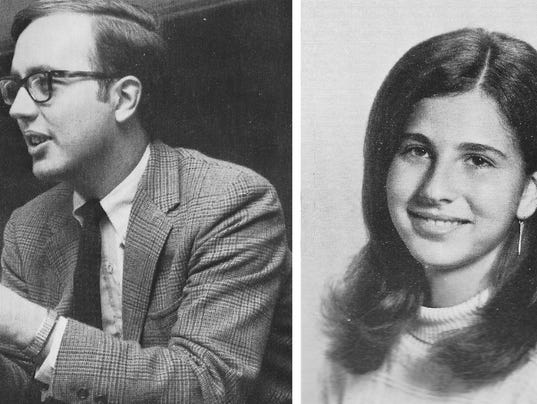

(Photo: Family photos)

We started our conversation in September 1967, when we both walked into an English classroom in Syosset High School, a sprawling building in a north shore suburb on Long Island, about 30 miles east of Times Square.

One of us, starting her junior year, sat at a student desk, the kind with a large flat arm that swings up when you have to write. The other, just three years out of college and beginning his second year at Syosset High, took his place at the teacher’s desk and passed out a lengthy syllabus. Eleventh grade English was devoted to American lit.

Over the next nine months, in a classroom we can both still visualize, we and about 25 other students read dozens of novels, plays, poems and short stories. We argued about these works — about plot and characterization, about the authors’ themes and intentions, about what symbolism meant and whether it even existed. We analyzed structure and referenced historical contexts and uncovered broad cultural implications in the commonalities shared by individual works.

One of us, along with her classmates, wrote papers that the other returned richly annotated, comments scrawled in hard-to-decipher green ink. But mostly what we did was argue.

At the end of senior year, Roberta asked George to sign her yearbook. “Keep in touch,” his inscription read. “I’d like to see who you become.”

That turned out to be our last communication for more than four decades. And it probably would have ended there, if not for Facebook.

Yes, Facebook. A few years ago, we began another conversation, or perhaps just resumed the original, when we found ourselves agreeing with articles people were posting about education. We both deplored the way teachers were being blamed — scapegoated, we believed — for failures in the educational system. We’d both been involved in education through the decades, though in different capacities, and quickly discovered that we’d reached many of the same conclusions about the issues dominating educational conversations: high stakes testing, school choice, vouchers and charter schools, academic standards, the Common Core, accountability, tenure, class size; the length of the school day and the length of the school year.

We agreed that the American education system was at an inflection point, generating controversy and disagreement across the social and political spectrum. The only issue people seemed to agree on was that the schools weren’t working. Or, at best, that they weren’t working as well as we wanted and needed them to work if they were to be, as Diane Ravitch has called them, an “engine of democracy.”

At times the problems seem insurmountable. Yet we knew there have been times when American schools did work — and places where they worked well. We met during one of those times, in one of those places.

Things were different in the late 1960s, of course. Government policies like the GI Bill that had sparked the post-war boom were still helping veterans as they bought homes and began families, creating the stable middle class powering America’s growth. This support included funding for education — witness the huge injection of funds for education after the Sputnik launch in 1957. And there was a sense that schools and learning were valued as ends in themselves, not merely as means to economic advantage. Teachers were still respected as leading members of the community, and very smart young people still entered the profession — some leaving other jobs, even Wall Street careers, to become teachers.

Other societal factors were not so different. Funding was just as inequitable as it is today, and schools serving the students who had the most trouble learning, the ones who needed the most support, were just as likely to be strapped for resources. Many communities — especially most on Long Island — were rigidly segregated. Teachers were underpaid compared to other professions, especially those involved in finance, by perhaps an even wider margin than today. Students were just as likely to feel pressured to succeed, and just as likely to choose instead to tune in, turn on, and drop out. Outside pressure groups, none of them educators, were just as likely to interfere with what was happening in the classrooms — protesting, banning books, even demanding curriculum changes.

But two aspects of the educational climate we remembered stood out: in Syosset, in 1967, the majority of the community trusted the teachers to know how to teach. And the community was committed to providing the resources to help the teachers do their jobs. Those were the differences, we agreed, that made the crucial difference.

“Maybe we should write a book together,” Roberta wrote one day, half in jest and somewhat nervously. It seemed a bold suggestion, verging on the presumptuous. She regretted it right after pressing the “send” button.

George wrote back almost immediately. “Maybe we should,” he said.

Roberta Israeloff, a writer and editor, is director of the Squire Family Foundation, which promotes philosophy in education. George McDermott is a teacher, writer and editor. This column is adapted from their new book,What Went Right: Lessons from Both Sides of the Teacher’s Desk, published Wednesday.

JOIN SL 2.0

SUBSCRIBE TO

SCHOOL LEADERSHIP 2.0

Feedspot named School Leadership 2.0 one of the "Top 25 Educational Leadership Blogs"

"School Leadership 2.0 is the premier virtual learning community for school leaders from around the globe."

---------------------------

Our community is a subscription-based paid service ($19.95/year or only $1.99 per month for a trial membership) that will provide school leaders with outstanding resources. Learn more about membership to this service by clicking one of our links below.

Click HERE to subscribe as an individual.

Click HERE to learn about group membership (i.e., association, leadership teams)

__________________

CREATE AN EMPLOYER PROFILE AND GET JOB ALERTS AT

SCHOOLLEADERSHIPJOBS.COM

New Partnership

Mentors.net - a Professional Development Resource

Mentors.net was founded in 1995 as a professional development resource for school administrators leading new teacher induction programs. It soon evolved into a destination where both new and student teachers could reflect on their teaching experiences. Now, nearly thirty years later, Mentors.net has taken on a new direction—serving as a platform for beginning teachers, preservice educators, and

other professionals to share their insights and experiences from the early years of teaching, with a focus on integrating artificial intelligence. We invite you to contribute by sharing your experiences in the form of a journal article, story, reflection, or timely tips, especially on how you incorporate AI into your teaching

practice. Submissions may range from a 500-word personal reflection to a 2,000-word article with formal citations.

You need to be a member of School Leadership 2.0 to add comments!

Join School Leadership 2.0