#5 Abandon This “Be Sure To Present Both Sides” Dogma

Despite everything I just said, I cannot remain complicit in this notion that any time there is an issue that is controversial in our classrooms, that we have to present “both sides.” To be sure, there are many times where there are two sides to a political issue. But as demonstrated in the last year and a half, there are plenty of competing viewpoints just within the Democratic and Republican Parties. Populism, neo-liberalism, progressivism, libertarianism, democratic socialism — these are all terms being used to describe various political beliefs. This is THE space to acknowledge that although we nominally function using a two party system, that does not mean there are simply two sides to issues like immigration, taxes, and entitlement reform.

Even more importantly, we have to be willing to draw lines in the sand and say that in some instances, there is just ONE side. Climate change is real. Vaccines do not cause autism. There is no evidence of widespread voter fraud in the 2016 Presidential Election. Barack Obama is a United States citizen. A perspective on an issue that has no factual basis has no place in a classroom. Period. I encourage debates and discussions in all of my classrooms, and I have often taken the perspective that the minority of the students are arguing to help balance the equation and challenge students to think about a topic from another angle. But I won’t play the “devil’s advocate” for something that simply is not true.

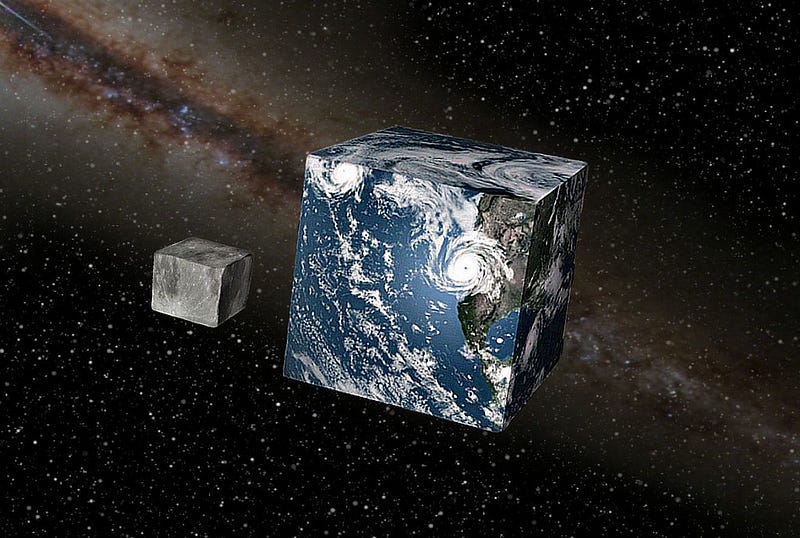

As important as it is that we teach students about exploring the perspectives of others, trying to find common ground, and encourage compromise, we also need to empower them to understand that those goals are only achievable when a) all parties have beliefs that are grounded in fact and b) everyone is operating within the norms and values that we expect and promote in our democratic society. The example I use when explaining this to my students is this: if someone argues that the Earth is flat, do we try and find common ground and compromise with them? Where is the middle in that “debate?” Do we ignore scientific fact and reach a middle ground conclusion that the Earth is a cube? No.

There are some things we cannot compromise on. Whether the Earth is round or not is an example. I’m not meeting Kyrie Irving halfway here. He is wrong.

This component is even more paramount now after the recent events in Charlottesville. White supremacy has no place in my classroom because it has no place in American politics. Nazism has no place in my classroom because it has no place in American politics. I am not going to roleplay a white supremacist. I am not going to ask my students to identify the common ground they might find with a Nazi so they can have nice, peaceful relations with them.

We didn’t compromise with these folks in 1945

Teachers are often understandably afraid to draw a hard line like I am proposing because of fear of pushback — from students, from parents, from the community. But if we are clear and purposeful in how we approach these issues, there is simply no ground for complaint. If a white student in my classroom told a student of color that they were inferior and that the United States was a country for white people only, they would be egregiously violating the student code of conduct and I would be well within my right to refer them to the office for the administration to punish them. So why would I create a space for those beliefs? Similarly, if a student said those things in my classroom and I did nothing, I would be in huge trouble for allowing a child to be racially harassed and intimidated. I feel very strongly that if I were to ignore the growth in political activity on the part of white supremacists and Nazis, I would be just as guilty as if I ignored it being directly said in my classroom.

I want to be very clear about something. Students have an undeniable right to freedom of speech, as clearly upheld in Tinker v. Des Moines. The Tinker standard is very clear that maintaining students’ rights to political speech in particular is critical, so long as it does not substantially disrupt the educational environment. But nothing that I am proposing is new or different than how we are operating currently. The wrongs of Nazism are already taught in United States History. Why not United States Government? The wrongs of the Ku Klux Klan are already taught in United States History. Why not United States Government? Furthermore, I think it is pretty clear that politics of hate, based on components of individual identity, is fundamentally disruptive to the educational environment. What if a student espoused their belief in eugenics (a component of Nazism) that people with “deficient” genetics should be killed by the state? How does that not fundamentally disrupt the educational environment of that classroom, especially if someone in the room receives special education services or has a family member with a physical or intellectual disability? And legal counsel for various school districts across the country have affirmed this interpretation that the articulation of hate based politics in the classroom would most likely constitute a violation of the Tinker standard because of the disruption to the educational environment.

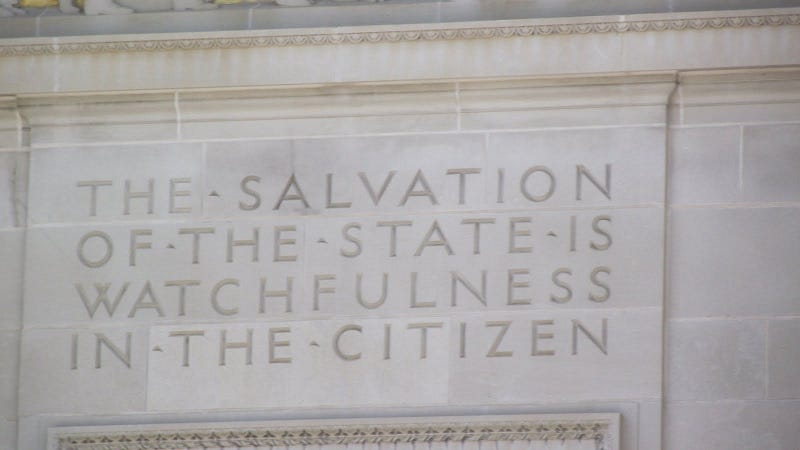

The United States prides itself on its unfettered access to political free speech. This is based on the principal that we should not let the state have the power to discriminate speech on the basis of content. That philosophy only works, however, if the citizen body then reaffirms the values we want to see in our society. Freedom of speech means you have the right to say it, but it does not mean you are free from consequences for your speech. Even as we speak, people that attended the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville are losing their jobs because the companies they work for do not want to employ people who publically profess ideas that go against the ethical beliefs of that corporation. As educators, we cannot pretend that this isn’t an issue in our country right now. As educators, we need to thread the needle on this delicate issue and confront this issue in a way that educates and empowers our students.

Ironically, I am well protected in this endeavor. During the early Cold War and the United States experiencing peak McCarthyism, Nebraska passed a statute (79–724) that outlined the standards for “Americanism” in Nebraska public schools. The usual stuff is there — recite the pledge, teach about important people in our nation’s history, teach the strengths of democracy. But of particular note is a requirement that all teachers educate their students on the “dangers and fallacies of Nazism.” So state law is on my side.

But I will say one final thing on this issue. I do think we need to address whywe have come to the collective conclusion that ideologies like Nazism and White Supremacy have no place in our society. Like what I mentioned with fake news, if we just tell kids that certain political ideologies are bad, what skill set have we equipped them with? We need to walk that fine line where we discuss what the beliefs are and why there is such a near universal rejection of them without doing it in a way that legitimizes their positions in the classroom.

Let’s Get to Work

My school is on the 4x4 block schedule, and our government and economics class is only a one semester course. So for me, each class is only nine weeks long. I plan on posting a follow up about how well I was able to put everything I just wrote into practice, because I’m not so naïve to think that I won’t hit some turbulence as I try and take on a new prep for the first time. I am excited to teach this class because I am deeply patriotic, and I fervently believe in the grand experiment that is American democracy. But in order for that ongoing experiment to be successful, in order for us to continue down that never ending quest to form a more perfect union, we need to be fearless in how we teach the next generation when it comes to government and politics.

You need to be a member of School Leadership 2.0 to add comments!

Join School Leadership 2.0