School Leadership 2.0

A Network Connecting School Leaders From Around The Globe

Do First Amendment Rights Apply to Students in School? Interview with Damon Krane via Peter Gray

Do First Amendment Rights Apply to Students in School?

Note to readers: Throughout the seven-year history of this blog, I have maintained a policy of no guest bloggers. Here is the first exception. This post was authored by Alex Walker, based on her interview of Damon Krane, founder of Free Student Press. The issue is so extraordinarily important, and the interview is so well done, that I had to break my rule in this one case. I also encourage readers to contribute to theFree Student Press Kickstarter compaign(link is external).

After reading this interview, please contribute to the discussion through the comments section, below. What do you think of this campaign to inform students of their First Amendment rights? Do you know of cases where students asserted their rights? If so, what were the consequences? How might we all contribute to this campaign to help students to execise rights that the constitution guarantees to all of us?

Bringing Unschooling to School: A conversation with Free Student Press founder Damon Krane

By Alex Walker; August 12, 2015

My son is only three years old, but even before he was born I was determined to raise him in a less conventional way. I knew homeschooling – or more specifically, unschooling – would probably be part of that design. My unconventional view of education is bound up with my attraction to a less mainstream, off-grid lifestyle. So, naturally, part of me longs to turn on my heel, leave all the worldly nonsense I detest about society in the dust while at the same time keeping my son out of the depressing feedback loop of the 19th century factory-style education system. As my son becomes an adult, I want him to have an experience that is itself significant, and not a contrived training for what is expected of him as an adult. I want him to have the guidance and resources available to become an independently minded person who can make empowered decisions for himself.

Yet I face an ethical impasse. To renounce the society you are born into comes with a price, and I find myself in a very privileged situation to even be considering homeschooling my son. As a white, middle class, college-educated American, I have both financial and social freedom to make relatively bold decisions in my life. And yet I am coming to acknowledge that the privilege I hold exists because of the very system I want to reject.

Furthermore, caring about my son means caring about the larger world he’ll live in and the society he’ll have to negotiate. Being an off-grid unschooler won’t make that world go away. Whatever protective buffers I create for my family, we will always be umbilically linked to the larger world, populated and sustained by individuals whose experiences may have been curtailed by public schools; flawed institutions that are symbiotically necessary to our current social framework.

While struggling with these issues, I was contacted by an old acquaintance, Damon Krane, who has been an activist, journalist, and grassroots social justice organizer for the better part of 20 years. His initiative, Free Student Press, amounts to an utter infiltration of independent thought within high schools, giving students the power to challenge norms, confront authoritarianism, and engage in constructive dialogue, while discovering and exercising their First Amendment rights to distribute independently produced publications that are often illegally inhibited by schools officials. By developing self-confidence and learning to work together, he believes that students can become empowered to build a better world.

Recently, Krane launched a Kickstarter campaign(link is external) to revive and dramatically expand Free Student Press. Already, his vision has been lauded by such prominent educators, authors and activists as Ira Shor, Noam Chomsky, Bill Ayers, and Dawson Barrett.

I recently spoke with Krane about Free Student Press and the relevance it might have to those interested in homeschooling and unschooling. Here is a summary of that interview:

So what is Free Student Press (FSP) and why is it relevant to people interested in homeschooling and unschooling?

Homeschooling and unschooling have a lot of appeal to parents who believe children and adolescents deserve more freedom to pursue their own curiosities and creative impulses than conventional schools allow. FSP is based on the same conviction. But instead of seeking to create totally separate alternatives to our public schools, or trying to reform national school policy from the top-down, FSP takes unschooling to school.

What exactly do you mean by that?

FSP starts from the assumption thatteenagers don’t need anyone else telling them what to do. What they need are more meaningful opportunities to express themselves, to make sense of their world, and to have an impact on that world. So FSP offers teenagers some very practical tools. The first tool is the knowledge schools typically hide from students about their First Amendment rights to distribute independent student publications at school.

More commonly known as underground newspapers or zines, these publications are produced by students, outside of school, and without using school resources. But then students can bring these publications to school and pass them out to their classmates on school grounds, during school hours. School officials can’t control the content, they can’tpunish students for writing things school officials don’t like, and in the overwhelming majority of cases school officials cannot legally prevent students from distributing independent student publications at school.

Within one of these publications, students can create for themselves a unique forum for public dialogue among their peers that is anchored to their experiences as students within their schools, and as young people within their communities. From my experience with these publications, I’ve learned that whatever disagreements students may have with one another, they tend to all want a place to discuss what they care about. So students learn how to manage this forum, because they’re committed to keeping it. They learn how to communicate better, because that’s necessary to change minds and have an impact. They learn about their peers and others’ perspectives, and the situation forces them to contend with others’ arguments. Finally, if school officials attempt to illegally censor a publication – as they often do – students get to learn how to defeat corrupt people in positions of power and authority through grassroots organizing.

And the best part of FSP’s approach is that we don’t have to wait until we’ve changed our schools, or until we’ve built better large-scale alternatives. Instead, we literally turn public schools into an opportunity for a massive unschooling campaign – one that not only enriches learning and improves young peoples’ lives, but which also dramatically increases Americans’ capacity to create a freer, more just society.

Let’s back up a bit and talk about students’ legal rights to do this. Are student press rights just a matter of the First Amendment, or of court decisions and/or other legislation?

The First Amendment was a concession early American elites granted in order to get the Constitution ratified. It really didn’t mean anything in practice until mass movements of ordinary people made it mean something – and that’s true for student press rights, too.

Back in the mid 1960s, a group of families in Des Moines, Iowa decided to express their opposition to the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands. Some of their kids wore these armbands to school, for which the children were threatened with violence by school officials and then promptly kicked out of school. The families and allied individuals and organizations fought back, and eventually this resulted in the 1969 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District. The Tinker decision did several things. Most important for FSP, it established the right of public high school students to distribute independent student publications at school.

Are there any legal limits placed on what students can do with these publications?

Independent student publishers and journalists are still bound by the same laws as professional journalists, publishers and everybody else when it comes to stuff like libel, invasion of privacy, obscenity, copyright infringement, and so on. But there is only one additional legal restriction that applies to independent student publishers at public schools.

School officials may only attempt to prevent distribution of an independent student publication if they can show there is a very high probability that the either the contents of the publication or the manner of its distribution would cause a severe disruption of official school proceedings or invade the rights of others. What 46 years of case law following Tinker has made clear is that it is extremely difficult for school officials to meet this standard.

If students have had this right since 1969, why am I just hearing about it now?

It’s not just you. Practically everyone is unaware of this.

For nearly a half century since Tinker, illegal censorship has continued to run rampant in our schools, as documented by groups including the Commission of Inquiry into High School Journalism, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Student Press Law Center. But the many reported cases of illegal censorship are just the tip of the iceberg. They don’t tell us about all the kids who were lied to about their rights at school, or simply not informed, or students who never reported illegal censorship because they didn’t know it was illegal.

Take me and many of our high school classmates. During our senior year some sophomores created a little zine they called Hide and Go Speak. As soon as the students passed out their first issue, they were called down to the principal’s office and told they could not hand out a student publication at school unless they first allowed the principal to edit its contents. Since they had not done so, they were all punished with several after school detentions, and that was the end of Hide and Go Speak. That’s miseducation and illegal censorship, but none of us knew better, so it was never reported.

So what happened when you first put the idea of Free Student Press into practice?

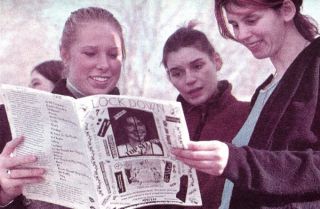

Within three weeks of our first outreach event, the very first group of high school students Lisa and I worked with produced a publication called Lockdown. On page one of their first issue, Lockdown’s creators accurately explained their First Amendment press rights and the Tinker decision.

And how did the school respond to Lockdown?

The principal threatened to suspend all of the students involved if “anything like this ever turns up again.” Then he informed the family of Lockdown’s lead publisher, Devin Aeh Canary, that a suspension would likely prevent her from becoming class valedictorian. Later, school authorities falsely accused the students of promoting drugs and violence through their publication, and local police were called upon to illegally break up a meeting about the paper the students were trying to hold at a public park. The superintendent, meanwhile, issued a press release declaring members of FSP irresponsible outside agitators who had made children feel unsafe at school, and he pressured officials at Ohio University (where I was an undergraduate education major) to encourage me to stop FSP’s work.

The conflict was pretty intense, and it lasted for nearly four months. But with FSP’s support the students mobilized so much community support that they completely defeated both their school administration and local police. The students kept publishing Lockdown, and the school’s principal resigned. FSP went on to work with more high school students and independent publications in the years that followed. However, officials at all of the five districts we worked with remained opposed to teaching students their press rights, publicly refusing to include accurate information in their student handbooks after FSP audited the handbooks a few years after the Lockdown controversy.

Why do you think censorship and deception about First Amendment rights are so common in public schools?

Public schools are supposed to be how we teach Americans constitutional rights essential to American democracy. But the design of our schools is at odds with that mission.

Our schools are designed to carry out what Paulo Freire called the banking concept of education. Within the banking concept, students are considered empty containers for a teacher to fill up with deposits of whatever information authorities have deemed valuable.

The first problem with the banking concept is that from the time we’re born, we human beings have our own curiosities and creative impulses. We want to figure out and consciously shape both ourselves and our world. But in the banking concept, these aspects of human nature are the enemy. They’ve got to be beaten down and suppressed so that students can be filled up with whatever is on any given day’s lesson plan.

For the banking concept to be implemented students must be silenced and made powerless. In contrast, independent student publications give students a voice and a means of developing power. That’s why our schools usually oppose student press rights.

You worked through FSP from 1999 through 2006 with students in Southeast Ohio. Now you’re trying to launch FSP in four Southern states over the next two years, and then take FSP nationwide. Tell me more about that plan.

If the Kickstarter campaign(link is external) reaches its goal, I’ll begin traveling to several college towns in Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina and South Carolina. In each town, I’ll recruit ateam of college student activist-volunteers to assist me with outreach and working with the high school students in their areas.

Once we’ve established contact with interested area high school students, we’ll hold two separate weekly meetings in each town – one for just the local FSP team, and one with the local FSP team and the local high school students. In the beginning, I’ll be leading FSP’s work with each group of high school students. But as the skills of the local team members become more advanced, they’ll gradually take over from me, freeing me to launch FSP in additional towns.

In the meantime, I’ll try to facilitate online networking between the different student publications, and I’ll help the students access the additional resources of other press rights advocacy groups like the American Civil Liberties Union and the Student Press Law Center.

Finally, I’ll be chronicling FSP’s work in a book. After this new two-year phase is completed, I’ll get the book published and use it to try to convince major funders and national organizations to expand FSP all across the country.

I can see this being something that homeschooled teenagers would enjoy and benefit from being a part of. Do you foresee FSP collaborating with and reaching out to kids who are not educated at school, but who want to learn about their rights and how to organize and engage in a more meaningful dialogue within their communities?

Homeschoolers – along with private school students, who aren’t afforded the same press rights as public school students (except by California’s Leonard Law) – can attend FSP meetings and connect with independent student publishers at the public high schools in their area. This gives homeschoolers the opportunity to submit writing and artwork and even participate in governing student publications. So the experience can benefit homeschoolers and give them a great opportunity to interact with other young people.

How can people support this work?

The Kickstarter campaign(link is external) needs to reach its goal by August 24, so I encourage everyone who supports this work to donate immediately and to tell all their colleagues, friends and family to do the same. This only works if a lot of us pitch in. But if this campaign succeeds, its impact will be tremendous.

____________

NOTE: This is a condensed version of a longer interview. To learn more about what the digital age means for independent student publications, the situation of students at private schools, and critiques of the banking concept of education, see the full interview, here(link is external).

___________

BIOS:

Alex Walker is a stay-at-home mother to a three-year-old son. Formerly a figurative artist and portrait painter, Alex is fascinated by sustainable architecture, homeschooling, gardening, and anything involving creative design. She is following her intention of learning more about human rights and progressive values and movements, as well as becoming a practitioner of ecological living. She lives with her son and husband in Littleton, Colorado and is thoroughly enjoying what the state has to offer.

Damon Krane is co-founder and director of Free Student Press. He has worked as a news reporter, opinion columnist, magazine editor, communications director, non-profit director, grassroots organizer and activist, journalism educator, and business manager. Much of his writing is archived at http://damonkrane.com(link is external). He is also a visual artist, specializing in black and white pencil portraits of people and pets athttp://fineartpetsketches.com(link is external) He lives with his wife in Atlanta, Georgia.

JOIN SL 2.0

SUBSCRIBE TO

SCHOOL LEADERSHIP 2.0

Feedspot named School Leadership 2.0 one of the "Top 25 Educational Leadership Blogs"

"School Leadership 2.0 is the premier virtual learning community for school leaders from around the globe."

---------------------------

Our community is a subscription-based paid service ($19.95/year or only $1.99 per month for a trial membership) that will provide school leaders with outstanding resources. Learn more about membership to this service by clicking one of our links below.

Click HERE to subscribe as an individual.

Click HERE to learn about group membership (i.e., association, leadership teams)

__________________

CREATE AN EMPLOYER PROFILE AND GET JOB ALERTS AT

SCHOOLLEADERSHIPJOBS.COM

New Partnership

Mentors.net - a Professional Development Resource

Mentors.net was founded in 1995 as a professional development resource for school administrators leading new teacher induction programs. It soon evolved into a destination where both new and student teachers could reflect on their teaching experiences. Now, nearly thirty years later, Mentors.net has taken on a new direction—serving as a platform for beginning teachers, preservice educators, and

other professionals to share their insights and experiences from the early years of teaching, with a focus on integrating artificial intelligence. We invite you to contribute by sharing your experiences in the form of a journal article, story, reflection, or timely tips, especially on how you incorporate AI into your teaching

practice. Submissions may range from a 500-word personal reflection to a 2,000-word article with formal citations.

You need to be a member of School Leadership 2.0 to add comments!

Join School Leadership 2.0