A MiddleWeb Blog

I believe in teaching the READER, not the READING.

In this post, I want to share some of the principles and practices for teaching whole-class novels that I’ve developed and that help me translate my belief into action.

There’s no perfect way to do this. These are teaching-hardened techniques that work in my classroom. I hope you’ll share your own thoughts and ideas in the comments. This could be a good summer chat.

A few of my earlier posts that connect here include Whole Novels or Choice Reading? Or Both? and also Resolved: Amp Up the New Year!

1. I use whole-class novels as a community building and learning experience. Not as a means to formally assess students. Because we read the book together, we have a touchstone to refer back to in future class sessions. Not every student loves every book we read, but they all experience growth and gain some appreciation for the author’s writing ability.

What’s more, it makes me happy as a teacher that nearly all of my students have readWonder in elementary school, and will read To Kill a Mockingbird later in middle school. There are some texts that have such deep meanings that I consider an education without experiencing them incomplete.

What’s more, it makes me happy as a teacher that nearly all of my students have readWonder in elementary school, and will read To Kill a Mockingbird later in middle school. There are some texts that have such deep meanings that I consider an education without experiencing them incomplete.

In my mind, this is no different from my colleagues in other disciplines providing foundational knowledge in the periodic table, the quadratic formula, or the Civil War as a starting point for digging deeper into their subject. These novels are worth reading because they can lead to so much more.

2. I want my students to read like writers. So we use our study of the text to explore the writer’s craft. I start from the foundation that every sentence in a novel has a purpose and was deliberately included. We talk about WHY the author may have written what he/she has and HOW they have structured the novel to achieve their desired goals. We appreciate their use of the language and try to emulate our favorite parts.

3. I want to honor their adolescent attention span. I have a short attention span, too, which greatly benefits my middle school students. I do not spend any more than 3 weeks on a novel. What’s more, we only read one novel per marking period together.

This means that in my current situation of teaching 6th grade in trimesters, we have three community reads during each period, for a total of 9 to 10 weeks. This leaves plenty of time for other activities. I find this time investment reasonable because 75% of the school year is left for choice reading and writing activities.

4. I provide lots of “framing” for the text. This can be historical context, current examples of the theme in the world, the author’s background, and “topic floods” (providing students with multiple bits of information related to key topics of the novel) to eliminate possible barriers to understanding.

Often students will say they don’t like a book they read on their own, but that is because they don’t always understand what is going on. To illustrate, when I taught The Outsiders to eight graders, they could absolutely relate to adolescents struggling to find their place in society and they only needed a little background knowledge about the time period to be fully invested in the novel.

I now teach sixth-grade all-girls classes, and we read a wonderful novel by Lensey Namioka entitled Ties That Bind, Ties That Break about a young girl in pre-revolutionary China who refuses to have her feet bound and the consequences she faces as a result.

I now teach sixth-grade all-girls classes, and we read a wonderful novel by Lensey Namioka entitled Ties That Bind, Ties That Break about a young girl in pre-revolutionary China who refuses to have her feet bound and the consequences she faces as a result.

This leads to rich conversation about unrealistic standards of beauty, going against family traditions, and acting on your convictions. All of these are invaluable when educating future female leaders. By the end of the year when we read Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, their profound discussions about racism and its legacy are deeply moving and worthwhile.

5. I choose a book that is at the reading level of the majority of my students. But that book is also an engaging work of literary merit such as a Newbery honor/award book. For those for whom my chosen text is a bit of a stretch, I incorporate many scaffolding and support techniques including audio books, partner reads, read aloud, and parent involvement to ensure they can access the material.

Conversely, I disagree that those students who are not challenged by the book’s reading level are getting less out of it. For me, rigor is the depth of thought involved in the process and not the decoding of the words on the page.

Most of what we do is open-ended, and my students take the discussions to incredibly insightful levels. Even those children who did not quite understand what they read eagerly contribute to the discussion because they are interested in the concepts.

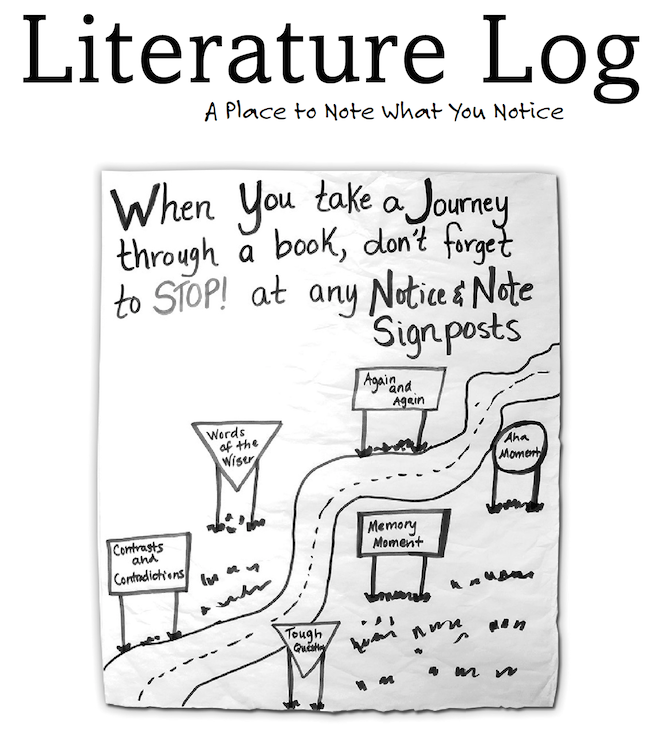

6. I gradually release responsibility as the year goes on. In my class, for the first novel, students lead the discussion of each chunk of text based on Notice and Notesignposts they have found.

6. I gradually release responsibility as the year goes on. In my class, for the first novel, students lead the discussion of each chunk of text based on Notice and Notesignposts they have found.

For the second novel, we focus on a couple of signposts, the chunks of text are larger, and students bring in their own questions to ask of peers. During the third novel of the year, students read the entire novel first and are then grouped in Book Clubs to allow for more discussion time.

7. I allow students to read ahead. The proviso is: they do not give “spoilers” during the discussion. They have been very good about honoring this policy. If we get partway through the book and they just could not wait to finish (as often happens), I will allow them the time to work in a small group to discuss things that happened after the chapters the rest are discussing. Or I chat with them individually after class with what they are bursting to talk about.

8. I find a literacy focus and learning target for reading.Students can’t hit a bullseye if they don’t know the target. For me, the magic bullet in making sure all students can explore and appreciate the novel in depth has been incorporating Beers and Probst’s Notice and Note into the mix.

I cannot say enough about how much I adore their book, and I have written several posts on my personal blog about it. Ariel Sacks uses three levels of questioning: literal, inferential, and critical. Chris Lehman and Kate Robert write about Lens, Patterns, and Understanding in Falling in Love with Close Reading.

It doesn’t matter which method you use to help your students to understand and appreciate the text. They all have merit. However, you will notice that none of these authors advocates the use of study guides, comprehension questions at the end of the every chapter, memorization of vocabulary words out of context, and endless worksheets. You don’t want to bury your students under a blizzard of worksheets.

9. I incorporate writing assignments and active experiences. Both tie into the book and complement the text. For example, we read Walk Two Moons, and there is a chapter where the mother explores the importance and origin of her name. We then read “My Name” by Sandra Cisneros and “Isn’t My Name Magical” by James Berry, and they write their own creative piece about their name.

9. I incorporate writing assignments and active experiences. Both tie into the book and complement the text. For example, we read Walk Two Moons, and there is a chapter where the mother explores the importance and origin of her name. We then read “My Name” by Sandra Cisneros and “Isn’t My Name Magical” by James Berry, and they write their own creative piece about their name.

You will note that these are not what Donalyn Miller calls “Language arts and crafts.” No dioramas, no character drawings, no book jackets, no travel brochures. I use authentic, meaningful, relevant writing experiences to draw them deeper into the text as well as allow for personal connections to be made.

10. I grade almost nothing during this time. At the end, there is a reflective writing piece as well as some kind of literary analysis writing, but students are ready for this based on the rich discussions they have experienced.

There’s no perfect way

There is no perfect system for teaching everything we need to teach in the limited amount of time we are given. But this way of teaching whole-class novels allows me to achieve my teaching objectives without killing the novels and/or monopolizing the entire school year with these experiences.

In the years I have been teaching novels this way instead of as a nine-week worksheet, I have come to love talking about books with my students. I hope you experience book love in your classroom too.

You need to be a member of School Leadership 2.0 to add comments!

Join School Leadership 2.0