The push for high-performing college graduates and non-teachers from other professions to enter the classroom has reached an all-time high in the past few years. Proponents of “alternative entry” see it as a fast way to send motivated, knowledgeable instructors into schools—particularly high needs schools and subjects like math and science—but their inexperience and high turnover rate has drawn fire from critics.

- Ben Bradford tells the tale of two teachers from one alternative entry program, and takes a look at what it means to send the least experienced teachers into the most challenging schools.

“It’s hard learning how to teach, and there is, indisputably, there is time lost catching up,” says Arthur Gribensk, who taught high school biology for a year after graduating from UNC-Chapel Hill. “I definitely, unfortunately, was not nearly as good a teacher my first semester for my students than I was for my second and that’s something I regret. And, I can’t give them that time back.”

While Teach for America is the most well-known, North Carolina schools feature several alternative entry programs, including NC Inspire, NC Teacher Corps, and TEACH Charlotte. These programs take participants through a few weeks of “boot camp” before the school year begins. Would-be teachers can also apply directly for a provisional license through a state process called lateral entry. That requires no educational training.

The state’s new education law includes two separate provisions to expand alternative entry; one lowers standards for technical professionals to receive licensure, and the other directs the state to more aggressively place alternative entry teachers into schools with math and science needs.

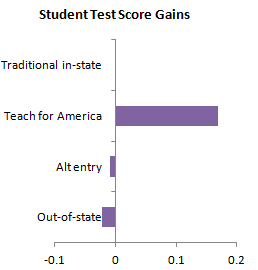

Some alternative entry programs, Teach for America in particular, have a good track record when compared to other educational preparation, including traditional undergraduate and master’s degree programs. Studies consistently show Teach for America participants getting the best results of first-year teachers.

Vanderbilt education professor Gary Henry has authored many of those studies, but he says that misses the point, because experienced teachers are better still.

“Teachers after five years will be better than any other teacher during their first year or even their first or second year,” says Henry.

The problem, Henry says, is that most alternative entry teachers never reach that high water mark of five years. TEACH Charlotte requires a one-year commitment. Teach for America requires two. Henry says few stay much longer. In TEACH Charlotte’s case, 30 percent didn’t teach a second year.

There are studies that disagree with the importance of teacher experience. In 2008, the Urban Institute issued a study titled “Despite Little Experience, Teach for America Educators Outpace Vete....”

The short training times and low financial cost lower barriers for entry, but also for exit. Because many programs target the most high-need schools, Henry says the least experienced teachers enter the deepest end of the pool.

“What happens is that our most challenging schools have the most inexperienced teachers and the highest turnover rates, with teachers either leaving the profession or leaving to go to less challenging schools, which means we have a revolving door of teachers in our most challenging environments,” says Henry.